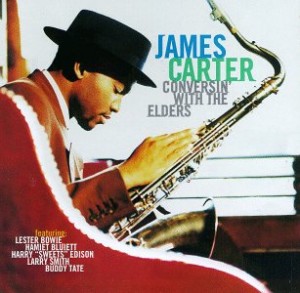

James Carter – Conversin’ With the Elders Atlantic 82908-2 (1996)

A great many people play classic jazz tunes like “Parker’s Mood,” “Lester Leaps In,” “Naima,” and “Moten Swing.” Precious few put out albums with those songs set beside the likes of Anthony Braxton‘s “Composition #40Q” and Lester Bowie‘s “FreeReggaeHiBop” (AKA “Ska Reggae Hi-Bop” as recorded by Bowie with The Skatalites) and find ways to make each and every performance dazzle. But James Carter does just that on Conversin’ With the Elders. Working with an assortment of elder statesmen of jazz from whom he has drawn inspiration, he is never intimidated for a second. His tone is brash as always. Yet what marks this album as something special is that it connects Carter’s music to a sense of context. Nicholas Boyle, writing an introduction to a Selected Works English-language edition of writings by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, said that “Goethe — it is especially evident in his novels — was aware that the meanings that make up our lives may come from outside us. *** [W]e find ourselves by giving up the search for ourselves and finding instead the world — a world which is there for us . . . .” And so it would seem with James Carter too, for he is never bound up with distancing himself from tradition. He instead positions himself within a continuum represented by the songs and collaborators he works with. He is of course a recognizable force within that continuum, such as how he at times fractures the familiar melodies of some of these songs and squawks his way through the more conservative material, but it is precisely by working with, rather than against, the bits and pieces of musical history you have here that he achieves something much greater than just another futile attempt to make a complete break with that which came before. In that sense this is the final frontier of music, where everything is put on the table and what was already there can’t be ignored. Music like this actually takes more effort and maturity than something created in a bubble, because it requires equal parts deferential respect and confident innovation. Oh, and it just sounds great! This is a lot more interesting than hearing some supposedly out-there musician playing what amounts to the same thing over and again and just calling it “free” or some conservative partisan painting himself or herself into a very tight corner of rigid post-bop reconstructions.