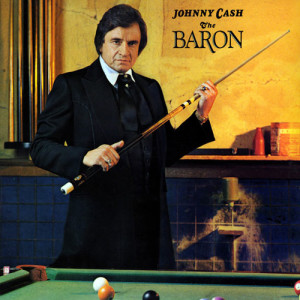

Johnny Cash – The Baron Columbia FC 37179 (1981)

For The Baron, Cash teamed up with producer Billy Sherrill, the man most responsible for the popular “countrypolitan” style used with Charlie Rich, George Jones, and others to great success over the previous decades. The Tennessee Three were not on the album. It was a more ornate studio band instead. The results are pleasant if plain, as the countrypolitan style was definitely getting a little dusty by the early 1980s. Cash also admitted in his second autobiography that he and Sherrill didn’t exactly put in a tremendous effort. The best thing here is the opening title track, which seems pretty clearly an attempt to mimic the success of Kenny Rogers‘ The Gambler but based on the story a pool shark instead of a card shark. A version of Tom T. Hall‘s “Ceiling, Four Walls, and a Floor” is decent too. “Chattanooga City Limit Sign” is one offering more in the rollicking novelty-song style of “One Piece at a Time.” The worst thing here is without a doubt “The Greatest Love Affair,” the most cloyingly patriotic song cash probably ever recorded (and he recorded a lot of that garbage, so this is saying a lot). Not an essential Cash album, but also not the worst he’s done.

Historian Jefferson Cowie has written about the sorts of socioeconomic changes that took place in the 1970s, as evidenced through music and film (Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class [2010]). In an article, “That ’70s Feelin’,” he described the way a dominant expression of working class sentiment in popular media became the individual “psychological release” of the character Howard Beale in the film Network (1976), when he exclaimed, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” without offering that exclamation in service of building any sort of program of positive action (after all, Beale was manipulated and later killed in the film for standing in the way of the network’s new “The Mao Tse-Tung Hour” program). There was fragmentation and parochial infighting. Much of Cowie’s music and film examples draw from the influence of Richard Sennett & Jonathan Cobb’s The Hidden Injuries of Class (1973), which described the conditions that sort of gave rise to the re-birth of individualism and Tom Wolfe‘s “me generation”.

Cash made a series of albums in the late 1970s and early 80s that are fairly interesting when viewed through the lens of Cowie’s thesis. The Rambler, The Last Gunfighter Ballad, The Baron, Johnny 99 — all of these albums, in whole (like The Rambler) or in key songs, are structured around a lone individual. If there is a dominant narrative of the lone individual failing or having a bittersweet ending trying to break away from the claustrophobic confines of social structures, like in the films Rocky (1976) and Saturday Night Fever (1977) that Cowie highlights, Cash’s albums paint the loner as someone worn out by clinging to something of the past or looking to reclaim it. On The Baron, this characteristic is all over the title track, and even “The Hard Way” and “Ceiling, Four Walls, and a Floor“. The title track on The Last Gunfighter Ballad is about a shameless, fame-seeking gunfighter run over by a car as an old man, dismissed by latter-day society as part of the lunatic fringe. The entire album The Rambler involves Cash playing a wise old man archetype, teaching and helping those he encounters on his journeys. Even on Johnny 99 the Springsteen song “Highway Patrolman” concludes with the lines, “man turns his back on his family / he ain’t no good.” While the circumstances of these sorts of songs deal with lone individuals, they offer a different treatment than what Cowie talks about by sympathizing with a need for community and lamenting anomie. In this way, Cash was going against the grain amid the rise of the Carter-Thatcher-Reagan era. This might be one partial explanation for his diminishing commercial success in the era.

Cowie’s thesis also parallels and draws from Christopher Lasch‘s in The Culture of Narcissism (1978), which explained how, by the 1970s, individualist narcissism had displaced traditional symbolic authority, as a byproduct of corporate bureaucracy. (Lasch’s thesis is probably best viewed as a supplement to Jacques Lacan’s thesis that “discourse of the university” had displaced “discourse of the master” during the 20th Century, with Lasch espousing quasi-populist socially conservative leftism informed by psychoanalysis and Lacan). Here, Cash’s invocation of the aristocratic title “the baron” is a direct reference to a relic of symbolic authority from the past, and the namesake in the song encounters a young individual (his son) representing the new individualist narcissism, who was denied the opportunity to receive the “wisdom” of the paternal figure — thereby breaking from (patriarchal) tradition and its symbolic structures.

Much, much later, when Cash triumphantly made a “comeback” with his American Recordings album in the 1990s, circumstances had changed. The usual story is that producer Rick Rubin came in and revived Cash’s career. But, aside from Rubin’s indeed excellent work as a producer, this marketing ploy falls apart on close examination. A lot of the renewed success came from timing. Cash was hardly singing differently on American Recordings than he was on The Mystery of Life, which was the commercial nadir of his long career. But on American Recordings, the songs he was singing showed very different choices than what he had offered on flops like Johnny Cash Is Coming to Town. By the mid-1990s, the cracks were showing in the neoliberal political order that went hand-in-hand with the socioeconomic conditions Cowie was writing about. Audiences were maybe believing a bit less in the narrative preached by the loner raging against the system. Rocky V (1990) was a bomb. But Cash, still around, and still in his own way questioning the very notion of the individual triumphing against the social order, was back to singing about the downtrodden, lost individual in need of others for support — “Bird on a Wire,” “Drive On,” … Is this not just what Cash was singing about in the late 1970s too?

It might be possible to argue that the particular style of austere acoustic guitar playing on American Recordings is better or more attractive to audiences, but we should also consider the point of reference of the audiences that made the entire American Recordings series of albums more successful than the past efforts. Johnny Cash now had an element of danger. He may have had the image of the “man in black”, who did prison concerts and was beloved by the mean, dangerous convicts locked away there, but he also was a guy who cultivated that image to supposedly help the poor and deprived (he even wrote a song about why he is the “man in black”!). He wasn’t using the outlaw image just to bolster his own situation (though, obviously, he was doing that too; he was trying to sell his recordings after all) but to call attention to a lack of solidarity. Those efforts were still shot through with contradictions. The closer “The Greatest Love Affair” on The Baron is patriotic garbage, the sort of nationalistic chauvinism that is squarely at odds with the egalitarian impulses elsewhere in Cash’s music — does equality for all really stop at arbitrary borders on a political map? Though the kind of bastardized patriotism of a song like that was one of the only ways the working class had left to express solidarity in a world of bullshit jobs and self-interested hedonism. And let’s look further at the man’s American Recordings comeback, to the second installment, Unchained. Songs like “Rusty Cage” and even “Rowboat” revive the theme of the loner raging against the system. And even “I’ve Been Everywhere” vaguely fits that mold as well. Those tunes lack the appeals to solidarity and revival of old systems of community and family found elsewhere in Cash’s work. But is it telling that many consider Unchained a lesser album in the American Recordings series?

No doubt, The Baron is a weaker Johnny Cash album. But given a close examination, there is is something to be admired in Cash’s intransigent support of his old New Deal style social optimism against the great weight of the Carter-Thatcher-Reagan era’s neoliberal onslaught against it. Cash wasn’t overtly political in his music, but his politics were intimately a part of what he did, apparent as much in what he didn’t do as anything else. So, in a way, a meaningful appreciation of Johnny Cash at the peak of his powers and popularity should create some obligation to look at Cash when his outlook on life and what he represented was under attack, when it would have taken superhuman efforts to swim against the current from his position. Does “The Baron” even take on something of an autobiographical tone? In a way, too, Cash and Sherrill making a countrypolitan album in 1981 is something like Harry Nilsson singing on “You’re Breaking My Heart” (Son of Schmilsson): “You’re breakin’ my heart / You’re tearing it apart / So fuck you.” It was maybe a populist cop out, in failing to reconnect with new audiences. But if what listeners wanted was hedonism, Johnny Cash was just raising his middle finger to them, like in the iconic photo of him by Jim Marshall from San Quentin Prison, who said, “John, let’s do a shot for the warden.”