Sonic Youth – Murray Street Geffen 493 319-2 (2002)

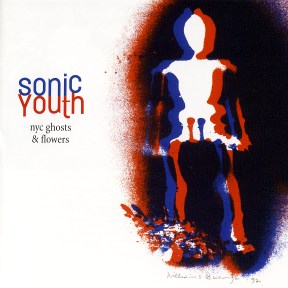

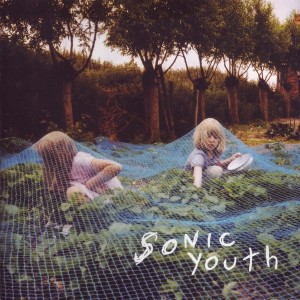

Murray Street is an album Sonic Youth always had in them, bouncing around. The sounds were just waiting to come out. When the timing was right, it appeared on record, but not before the timing was just right. They had to make the last few records (Washing Machine, A Thousand Leaves, SYR4: Goodbye 20th Century and NYC Ghosts & Flowers) first to line up the competing elements (noisy experiments and chilled-out mood music mediated by explorations of harmonics and overtones) that sort of reach an amiable compromise here. Looking back, though, they never reached this level of accomplishment on record again before the band’s demise.

The late 1990s saw Sonic Youth coping with being a rock music institution. That’s irony for you. Nothing on Murray Street sounds ironic, because of the group’s gift for anticipating the punch lines of jokes still being formulated in the minds of doubters. This was supposed to be the second of a planned trilogy of albums about Sonic Youth’s New York City haunts, which began with NYC Ghosts & Flowers but which never seemed to find its third installment, this nostalgic phase has nonetheless worked out quite well for the Youth. It finds “Plastic Sun” with Kim Gordon doing her best Patti Smith. And “Sympathy for the Strawberry” sounding like a forgotten Television song somehow recorded in the 1960s. Even “Rain On Tin” almost seems inspired by the Grateful Dead stopping by the Fillmore East. Murray Street is all New York City.

“Karen Revisited,” “The Empty Page” and,especially, “Rain on Tin” form the backbone of the album. The tempos are slow, and the guitar chords are softened at the edges with fuzzy noise that makes them sort of wash away one into the next. A slightly harder-edged counterpart would be Boris & Merzbow‘s live collaboration Rock Dream. But this venerable band needs a “Radical Adults Lick Godhead Style” too. It is the disc’s punch line, two-thirds through. The saxophones of Borbetomagus join the Youth to necessitate double checking that listeners are safely beyond throat-kicking distance. Then the album drifts into two more improvised numbers to close.

This album made Jim O’Rourke, officially, the fifth member of Sonic Youth. He was often “accused” of being a noisy guy. Yet he has a deep pop sensibility too. On Murray Street O’Rourke helped the Youth put together perhaps their mellowest album to date (some consider this a flaw of the album, because it deviates from their expectations). Having O’Rourke around brings out personality quirks rarely heard before from the Youth. For example, Lee Ranaldo’s jam band attitude sees more light of day.

The temptation in this part of Sonic Youth’s career, though, was to make a bunch of albums that mechanically rotate through each member’s slightly different interests. Sonic Youth spare us those gory (and boring) details. Murray Street cuts itself to proper form. The album comes across as well rounded and unified, varied yet whole. There is some brilliant O’Rourke-orchestrated noise on the 11-minute “Karen Revisited,” but not before delivering one of the best Lee Ranaldo beat/hippie epics. There is no abrupt rupture as the song changes direction. Mostly, though, the Youth are out to groove. Reconstructed surf and R&B riffs permeate the disc. Yet they are at the same time sublimated beneath electronic noise. There is considerably less snottiness than in the old days. That proves no loss. The subversively catchy songs almost belie what they are. This is inventive music that wants to be as endearing as anything you’ve heard before.

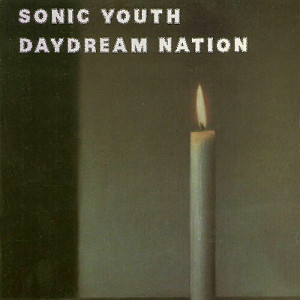

Murray Street is for everyone, not just Sonic Youth diehards. It refines and expands upon the ideas first sketched out on Washing Machine, making this the bigger accomplishment. There are enough layers to appreciate it both at first and over time. Murray Street is another disc to add to Sonic Youth’s pile of really good ones. It is tempting to say it (slightly) lacks the daring to make it one of their very best, but it has stood the test of time so well and is, to these ears at least, maybe a more welcoming listen that the acknowledged classics. Hell, maybe it is time to simply call this one of the band’s best.