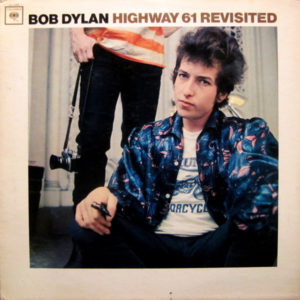

Bob Dylan – Highway 61 Revisited Columbia CL 2389 (1965)

Highway 61 Revisited was Dylan’s entry into the realm of superstardom. He had popularity that was entering the same leagues as that of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Bringing It All Back Home was massively popular, but Highway 61 confirmed that Dylan was no flash-in-the-pan success.

This is quite simply the single most essential Dylan album, and one of the most essential rock and roll albums by anyone from any era. The enduring importance of this album might be how it managed to be a rock album of substance, something with real weight and depth, not just tawdry entertainment. Unlike Bringing It All Back Home with an entire side geared toward folk rather than rock, Highway 61 Revisited focused entirely on rock. So much early rock and roll was easily dismissed as just dance music or hillbilly stuff without cachet in urban centers. This album was something else. It raised the bar for what rock music was (or could be) about. In a way, it helped give unprecedented legitimacy to rock and roll, without ever diminishing the intensity and energy and exuberance of the music. By this point, Dylan’s songwriting talent was unassailable. He had successfully fused blues rock with poetic lyrics that encompassed symbolism, American and biblical mythology, surrealism, literary references, and vivid imagery. The songs rarely “meant” anything in a literal sense. They were oblique invocations of certain feelings and images without a fixed and definite meaning. You can listen to these songs again and again and come away with a slightly interpretation each time. Roland Barthes wrote the following year in Criticism and Truth that “a work is ‘eternal’ not because it imposes a single meaning on different men, but because it suggests different meanings to one man…” So it was with these songs. Dylan’s approach was drawing huge influence from the writings of the Beats, incorporating that writing style into a rock and roll setting. The music still had a huge, driving syncopated beat, complete with just enough of the twang and grit to draw a clear line of influence from early rock and roll. He was supported by a studio band that included members of The Paul Butterfield Blues Band plus Al Kooper on keyboards. Kooper was not a keyboardist, but the recording sessions for this album made him one. Electric guitarist Mike Bloomfield has a strong presence that separates the sound of this album from others Dylan had recorded to this point (or what he did later, for that matter).

On “Tombstone Blues,” Dylan sings “the sun’s not yellow, it’s chicken,” invoking American slang in which both “yellow” and “chicken” refer to cowardice. Applying the terms to the sun, Dylan–in a way that epitomizes his songwriting at the time–says something that is perfectly plain but that doesn’t mean anything in particular. He turns the word “yellow” from a description of color into a slang reference to something that doesn’t really have a literal meaning when applied to the sun. But to follow this, you almost have to work backwards through the lyrics. In a nutshell, that’s Dylan’s mid-1960s songwriting.