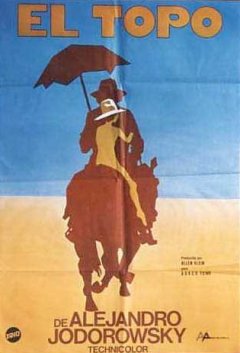

El Topo (1970)

Producciones Panic

Director: Alejandro Jodorowsky

Main Cast: Alejandro Jodorowsky, Brontis Jodorowsky, José Legarreta

For most viewers, El Topo (English translation: The Mole) will be the most bizarre western they have ever seen, and maybe even the most unusual movie of any genre they have ever seen. It has developed a cult following, and promoters claim it initiated the tradition of “midnight movies”, though a long dispute between the writer/director/star Alejandro Jodorowsky and the eventual distributor Allen Klein kept the movie largely unseen for decades. Although there are plenty of interpretations floating around, some sympathetic and some not, it is a movie that actually makes perfect sense from the standpoint of psychoanalysis (Jodorowsky studied psychology for a time).

Many interpretations see the movie as being about spiritual enlightenment. Maybe it is. But it is worth taking an entirely unsentimental look at it so see what other interpretations are possible.

The film opens with the black-clad gunfighter El Topo (Jodorowsky) riding into a small village on his horse with his naked son. The village has been ransacked, and there is blood and death everywhere. Jodorowsky locates the criminals responsible — they are led by a military officer. El Topo renders frontier justice and frees the surviving monks from the village and a woman. He leaves his son with the monks, and rides off with the woman. She convinces him to seek out and defeat four master gunfighters in the desert. He does so, and, finding them superior in skill, defeats them through trickery or luck. There is symbolism all over the movie. It is exaggerated symbolism, often religious. The master gunfighters each resemble a different religion. Along the way a black-clad woman whose voice is overdubbed with that of a man joins the pair. The last master that El Topo “defeats” actually kills himself, to prove to that his life means nothing. The woman in black then shoots El Topo, and his body is taken away by a band of physically handicapped or deformed people.

In the second half of the film, El Topo, now with a long beard and resembling some kind of spiritual guru, awakens from a long coma in a cave. He is living among the oddball people, who have been sealed in the cave by the residents of a nearby town. He is able to free the people from the cave eventually, after working as a street performer to beg for money to support them (Jodorowsky had studied as a mime). He is something of a Gandhian, of sorts. But upon releasing the prisoners of the cave, the townspeople murder them. This is a brutal representation of what social elites always do — segregate other classes, and when any possibility of upclassing and escape from ghettoization seems possible they take away that possibility through any means necessary.

Film scholars debate whether Jodorowsky is faithful to his overtly acknowledged influence from Antonin Artaud‘s “theater of cruelty”. He might be, or might not. The surrealist use of symbolism, in a way that both crystalizes and degenerates the meaning of those symbols, presents interesting fodder for that debate at the least. So many of the characters seem almost like Jungian archetypical images, essential representations of elements of a collective unconscious. Yet they live and die before us in the film. They are given gaudy, dramatic representation. But their deaths and flippant usage in the film suggests they are not eternal archetypes.

Jodorowsky is routinely dismissed by certain film critics as a charlatan. This is a rather common occurrence for an artist with anarchist tendencies. Such a position is (rightly) perceived as a threat to the status of critics, etc. who attempt to distinguish themselves on the basis of their position within an established social hierarchy. Jodorowsky is overtly attacking religions, of all kinds, and with it the very concept of a path pre-defined by a social hierarchy. But more than that, he also seems insistent that something else must be put in the vacant space, without demanding or asserting what that something else should be, precisely. The only demand, as such, is for the audience to work at the question.

It may be worth contrasting El Topo with Hermann Hesse‘s novel Siddartha (1922). Hesse’s protagonist leads a spiritual journey through asceticism, then hedonism, then to a middle way that finds him working as a ferryman at a river crossing. This end is a negation of self. The protagonist finds enlightenment. The book adopts aspects of hinduism, but is primarily buddhist. El Topo, in contrast, does not end with the protagonist finding enlightenment. He fails, if that is seen as his goal. But, he also goes from a gunfighter who really exists only to kill, to someone who takes a non-violent, self-sacrificing approach to helping others, falling back to killing (killing the wicked) before he then turns to kill himself, the killer. What is so different from Hesse is that Jodorowosky does not endorse a particular religion. He stages the “deaths” of the major religions, through the symbolic confrontations with the master gunfighters. The second half of his film takes place in the main character’s post-religious existence. He is burdened with the task of finding meaning that is not provided for him. Rather than simply regulating his empathy — not too much or too little, which is really what the “middle way” of buddhism is about — he tries to care for others and materially change their circumstances for the better.

But what El Topo does is to illustrate a very post-modern idea that through failure success eventually emerges. El Topo may die failing to save the people from the cave, but when he dies, a beehive appears, just as upon the death of each of the master gunfighters in the desert. He does not find any final answer or enlightenment, but just as the movie goes on after all of the first four master gunfighters die, there is the implication that there is more beyond the death of El Topo. His children survive to go on into the world further. His ultimate act is to destroy himself. His life, at the close of the film, is a negation.

The sort of definite resolution of a novel like Siddartha was rejected by many filmmakers in the 1970s. El Topo is one such example. Others are Federico Fellini’s Fellini Satyricon (1969), a Jungian interpretation of Petronius‘ fragmentary ancient Roman “novel” Satyricon that is one of the very few cinematic precedents for El Topo, Pier Paolo Pasolini‘s unmade screenplay St Paul, about the founder of the christian church, and Nicolas Roeg‘s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), based on the book by Walter Tevis, about an alien who comes to Earth to save his home planet only to get lost in wealth, celebrity and hedonism. Paul seeks to promote a revolutionary emancipation of christian believers, but ends up losing what he tries to advance under the weight of the contradictory pressures of the church as an institution. The alien in Roeg’s film (played by David Bowie) amasses wealth to build a spaceship to go back to his home planet, but his amassed wealth brings about his downfall as it calls attention to his plans and he is stopped by the vested interests of the establishment. Fellini said of Satyricon that his intent was “to eliminate the borderline between dream and imagination: to invent everything and then to objectify the fantasy; to get some distance from it in order to explore it as something all of a piece and unknowable.” There is much dreamlike symbolism of that sort in El Topo as well. Pasolini’s screenplay is the closest reference point to El Topo’s actions. The collective unity through christian ideals of “holy spirit” are ultimately incompatible with the institution of the church, yet are still noble efforts worthy of revisiting — Pasolini’s script transposed Paul’s life into the WWII era, with Nazis in place of Romans. El Topo tries to change the circumstances of the cave people, but he ultimately can’t change the bigoted townspeople who first trapped the others in the cave. The desire to free the cave people was still a good and worthy goal, but El Topo failed to achieve it. Just as in the first part of the film, he kills the bad guys. In this way, the failure is his own. He fails to move beyond such actions. Yet the entire thrust of the film is to suggest that one must try to fail, fail again, and fail better (to paraphrase Samuel Beckett).