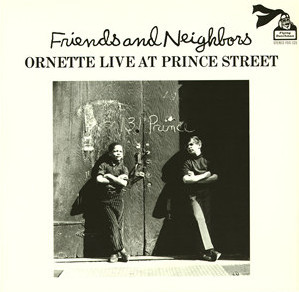

Ornette Coleman – Friends and Neighbors: Ornette Live at Prince Street Flying Dutchman (1970)

Ornette Coleman has had a strange and wonderful career. From the beginning, he was an iconoclast who sparked intensely divisive reactions. And yet, eventually, he was accepted as one of the most significant jazz musicians to date. But his legacy is a bizarre thing. He has recorded for a variety of record labels. He jumped around far more than most: they call Impulse! “the house that Trane built” and Miles Davis started on Prestige but stayed on Columbia for decades. Whatever the reasons for Ornette to jump around so much (I’m actually not familiar enough with the circumstances to comment), the result was a patchwork of recordings on different labels, many of which seem to have never been reissued, as of this writing, or have seen only fleeting reissues that soon went out of print. What this means is that listeners born long after Ornette’s career began often have no access at all to huge swaths of his recordings. In fact, even among Ornette fans, there are plenty who base their admiration entirely on his output for Atlantic records, which spanned a period of only about five years!

Ornette signed a one record deal with Bob Thiele‘s Flying Dutchman label, and released Friends and Neighbors, a live recording made sometime in 1970 at Ornette’s own New York City loft at 131 Prince Street on the Lower East Side. It was, at that time, still a seedy area abandoned by industrial concerns. But it had been in fits and starts a haven for jazz musicians, and would increasingly become a kind of magnet for jazz musicians in the 1970s. The Wildflowers series of albums from the later 70s documented the scene in all its glory. It was an independent-minded scene, with musicians doing everything themselves, from finding venues, promotion, to performance. This was partly out of necessity, as venues and record labels closed or were simply unwilling to support this kind of music. It was still a successful endeavor, for a time, and many musicians could support themselves this way while making the music they wanted.

This band is interesting. It has Ed Blackwell (d), Charlie Haden (b) and Dewey Redman (ts), but also, literally, friends and neighbors on vocals — the audience of people who came to the show get to participate. Redman’s time with Ornette is a strange one. Many recordings by the two have lacked reissues, and those they recorded for Blue Note were are notoriously off. But Redman added a unique contrast to Ornette’s sour alto (and his squealing trumpet and violin!), with a hefty tone that conveyed a sense of definite, conscious purpose. Ornette’s son Denardo had started playing drums in his father’s bands, but longtime collaborator Ed Blackwell is back behind the drum kit this time. Blackwell was a perfect match for Ornette’s style of music, and that is evident here. He brings in traces of bop styling while also having a light rolling lilt (a style he expanded through work with longtime Ornette collaborator Don Cherry). Charlie Haden is a rock. He’s fantastic here as always, with a warm inviting character that adds down-home grooves and cheerful optimism to the mix. It is Haden’s contributions, more than anything else, that make the music catchy and welcoming.

Some of the best material here is when Ornette is playing violin or trumpet (both versions of “Friends and Neighbors” and “Let’s Play”). Other musicians like Miles Davis (as mentioned in his autobiography) despised Ornette for playing instruments for which he was supposedly not qualified. This is one of the most fundamental differences between Ornette and everyone else though. He was an autodidact. And he was an anarchist. Teaching himself to play an instrument was the natural thing to do, from those perspectives. And he was bound by no one’s external ideas about who gets to decide what is the right or wrong way to play any instrument. So his self-taught techniques on violin and trumpet lacked the path-dependencies of people trained by others to follow certain performance institutions, meaning, especially, a respect for traditional hierarchies of teachers and students passed down from (only) respected elders to (only) younger players who respect and value the status of the teachers and reproduce the hierarchy. In a really classic anarchistic and autodidactic fashion, Ornette abruptly severs those institutional pathways and just plays however he wants. This almost always draws the ire of people (“conservatives” is the formal name) who demand adherence to social hierarchies that they have climbed, are climbing, or wish to climb. Some hate him for eschewing these hierarchies they are invested in, but that is precisely what other people love about Ornette! This is the most elemental reason for the polarizing reactions to the man’s music.

For a CD reissue of Friends and Neighbors, Dean Rudland provides excellent liner notes. He makes the pointed observation that Ornette’s music was “non-harmonic”. This might seem like a confusing statement about a musician who has dubbed his approach to artistic endeavor “Harmolodics”. But what it means is that Ornette generally does not dictate harmonic relationships in his compositions, at all. He establishes melodic progressions, but harmonic relationships arise only through the collective actions of all the performers during the act of improvising the songs. This is one of Ornette’s most radical concepts. He steadfastly refuses to establish relationships between performers. Everyone gets to play (transpose – the term Ornette tends to use) at his discretion, and the resultant harmonies become whatever they become. The performers don’t have complete discretion (this is not like some incoherent anarcho-punk morass). There is a structure offered, which is kind of an agreed direction (Ornette tends to call this playing in “unison”), but the implementation is equally open to the discretion of all the performers.

The man’s music was evolving through this period, and the use of trumpet and violin were the most telling signals that it would boldly go where no one chose to take it before. It is on the trumpet and violin songs that it is most clear that each performer is allowed to do anything and contribute equally. Ornette has no privileged position in the band. These things are contrasted by “Long Time No See” and the first part of “Forgotten Songs”, which kind of look back to what Ornette was doing back in the early 60s with the Don Cherry quartet or with the Izenzon/Moffett trio in the mid-60s.

While Friends and Neighbors might not be the most significant of Ornette’s recordings, it is still a really, really good one, very near the top of the stack. It shows him continuing to develop and refine the concepts that would culminate in Science Fiction (1972).